Disaster loss trends and the burden of proof

2 June 1, 2018 at 4:29 pm by Glenn McGillivrayWhen illustrating the general trend in disaster losses just a handful of graphs tend to get used the most.

When showing the international trend, the most frequently used exhibits are those published by Swiss Re and Munich Re.

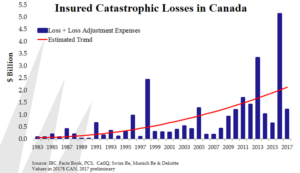

For the Canadian trend, the most frequently used graph is one published by Insurance Bureau of Canada (IBC).

The two most commonly used Swiss Re and Munich Re graphs look at both the number of natural disasters recorded per annum and the insured costs of those same disasters.

Swiss Re data begins at 1970 and Munich Re data begins at 1980.

Each company uses specific criteria with particular thresholds to determine what to include in their respective analysis.

For Swiss Re, the company uses insured loss figures (for ‘Maritime disasters’, ‘Aviation’ and ‘Other’) or Total Economic Losses or Casualties (‘Dead or missing’, ‘Injured, and ‘Homeless’). Munich Re uses similar metrics.

Many often ask why it is necessary to include dead, missing, injured and homeless in the data. Why not just use insured losses?

Casualty data is used primarily because insurance penetration is low in developing countries, so using insured loss data would only provide a good indication of loss experience in the industrialized countries. In order to get a full and accurate international picture of events and losses it is necessary to include a measure other than insured losses.

Unlike Swiss Re and Munich Re, IBC does not publish a graph showing number of Canadian loss events, only insured losses.

Bureau data begins at 1983. From that year to 2007, IBC uses data it collected itself through various company surveys conducted immediately after significant natural disaster events. It also uses various data from Property Claim Services (PCS), Swiss Re, Munich Re and Deloitte. After 2007, the Bureau only uses data from Catastrophe Indices and Quantification Inc. (CatIQ).

In all cases, the Swiss Re, Munich Re (both international) and IBC (Canada) data show a trend that is unmistakably upward: Over the periods in question, there have been both more natural disasters and higher associated costs.

But there are those out there (including climate change deniers) who maintain that the graphs are misleading, because while the data is normalized for inflation, no attempt has been made to take growth in population, economic activity, insurance premiums and development into consideration. When you factor these in, they argue, natural disaster severity may not be going up at all and, therefore, the charts may be giving a false impression.

Now, this is where the discussion can get messy to be sure.

Normalizing disaster loss data to include such factors as growth in population, economic activity and building stock is not a simple undertaking. Further, there are many problems with using simple measures like GDP or insurance premium growth as a normalizer.

For these and other reasons, I don’t want to go ‘there’ at this point, as such a discussion could not possibly be handled properly in a space like this. Further, it is something of a ‘Holy Grail‘ issue, as no one has adequately ‘cracked the code’ to be able to say with high statistical certainty that disaster losses are really going up or down when all factors are taken into consideration. It is what some might call a ‘wicked problem’.

But here is my take on why it is wrong to simply dismiss the Swiss Re, Munich Re and IBC graphs merely because they haven’t taken the above factors into consideration.

These graphs do not attempt to explain why disaster losses are going up, and no commentary is made on the apparent trend. They are simply plotting the number of events recorded and their associated costs. That is, the producers are not making any particular claims about the data, they are simply presenting the record (just as some plot trends in steel industry production, number of vehicles licenced or U.S. visitors to Canada). The disaster loss graphs are showing what insurers and reinsurers have paid out for natural disasters over a given time frame. That’s it.

Now, if the respective firms were using the graphs to make a particular argument, that would be a different story. They would then be expected to apply rigour to show a true underlying tendency and prove a cause.

However, producers of the graphs do not use them to attempt to explain the tendency or give a particular reason why the trend is going up. And when they do mention such things as climate change, they make no claim that that is the singular reason why disaster losses are rising (indeed, it is generally accepted by these companies and others that losses are going up primarily due to increases in insurable values, often in at-risk areas).

Now, if a third party claims that the graphs prove that the upward trend in catastrophe losses is solely or primarily due to climate change, increases in insurable equity or the price of beans, that’s their issue (and it is then incumbent on them to provide rigour-based evidence to back up their claim). But this has nothing to do with the original intent of the producer of the exhibit.

So how Swiss Re’s, Munich Re’s or IBC’s graphs are used (or misused) is neither the fault nor the concern of these entities, just as it is not the fault of a sporting goods manufacturer if one of their baseball bats is used to club someone over the head.

So, simply put, those who push to dismiss the graphs as inaccurate and misleading are barking up the wrong tree.

Note: By submitting your comments you acknowledge that insBlogs has the right to reproduce, broadcast and publicize those comments or any part thereof in any manner whatsoever. Please note that due to the volume of e-mails we receive, not all comments will be published and those that are published will not be edited. However, all will be carefully read, considered and appreciated.

Great discussion. Indeed, it would be wrong to simply dismiss the unadjusted-for-growth insured loss graph. But its not difficult to make the adjustments based on growth in premiums to better reflect the influence of the growth factor (e.g., in my recent paper “Evidence Based Policy Gaps in Water Resources: Thinking Fast and Slow on Floods and Flow” in the Journal of Water Management Modeling here: https://www.chijournal.org/C449 ).

Dr. Roger Pielke Jr. has promoted the use of adjusted loss to help understand trends in the US:

https://www.cityfloodmap.com/2016/12/book-review-rightful-place-of-science.html

And Munich RE routinely runs growth-adjusted loss trend charts as well – this blog post shows hydrological and meteorological losses for Canada for example:

https://www.cityfloodmap.com/2018/05/is-climate-change-making-flooding-worse_19.html

Adjusting for growth trends is routine and does not take away from the need to proactively address losses.

Bravo for pointing out “it is generally accepted by these companies and others that losses are going up primarily due to increases in insurable values, often in at-risk areas”. Lets add to that urbanization (+1000% in some GTA watersheds since the mid 1960’s) is THE driving hydrologic factor making risks worse:

https://www.slideshare.net/RobertMuir3/infrastructure-resiliency-and-adaptation-for-climate-change-and-todays-extremes

Unfortunately, even though Environment Canada Engineering Climate Datasets (version 2.3) show a “lack of detectable trend signal” in extreme rainfall, climate change is often cited by the insurance industry as the reason for the increasing trend. For example, Intact Financial this year reintroduced the disproved statement that weather events that used to happen every 40 year are already happening every 6 years despite this having been shown to be an arbitrary projected bell-curve shift, not based on any real data:

https://www.slideshare.net/RobertMuir3/storm-intensity-not-increasing-factual-review-of-engineering-datasets

The unadjusted chart has been used by third-party academics with insurance industry funding to state that regarding flood events “fundamentally the driver behind them at the base is climate change” and that we have “more rain in the system” whether at a Senate Subcommittee or on TVO:

https://tvo.org/video/programs/the-agenda-with-steve-paikin/assessing-ontarios-flood-risks

And the relative cause attributed to climate change is described as “a big percent”, when in fact 10’s of engineering studies on extreme rainfall trends show the exact opposite (i.e., southern Ontario data shows more statistically significant less extreme rainfall so ‘climate change’ has been a risk mitigating factor in some regions, according to data):

https://www.cityfloodmap.com/2018/03/extreme-rainfall-and-climate-change-in.html

To not be thrown in the ‘climate change denier’ pile (for citing data), I’ll add that I have done some of the most advanced future climate analyses and infrastructure resiliency stress tests of any engineer/municipality in Ontario, e.g., with this recent Water Environment of Ontario annual conference paper:

https://drive.google.com/open?id=15pc52qgbwOasSP5O1YU2GgEQLfqkjwbW

So we have to mange risk under climate change scenarios. But in southern Ontario, and other regions of Canada, data shows those predicted rainfall risks have not yet shown up in the extreme rain data (yet…).

There is no real problem with the popular unadjusted loss chart, because the values are not currently used in any economic analyses to support adaptation programs. But the constant mischaracterization of causes for these loss increases (typically cited as climate-related as opposed to urbanization-related) diverts attention from adaptation to mitigation measures, and resulting in less effective, direct solutions to lower losses.

For example in describing the unadjusted loss chart on TVO the Intact Centre on Climate Adaptation noted “Flooding is the number one cost to Canada in terms of climate change”.

Well put : “… if a third party claims that the graphs prove that the upward trend in catastrophe losses is solely or primarily due to climate change, increases in insurable equity or the price of beans, that’s their issue (and it is then incumbent on them to provide rigour-based evidence to back up their claim)”.

Intact Centre on Climate Adaptation has not provided any such back-up, only generalized statements about annual precipitation trends that are not valid engineering-based extreme-weather statistics.

Recognizing that the misinterpretation of causes by third-parties is diluting effective loss reduction solutions, IBC and others should encourage such evidence, not only on causes but on proposed costs-effective solutions. Third parties have prescribed green infrastructure like bioswales and permeable pavement to mitigate climate change and to adapt when rigorous analysis shows such measures:

1) do not move the dial in terms of reduce average annual damage reduction (0.07% river flood damage reduction in the US if all new development adopts this green infrastructure):

https://www.cityfloodmap.com/2018/06/watershed-scale-flood-damage-reduction.html

2) are prohibitively expensive considering capital costs (e.g., to retrofit Ontario alone with green infrastructure would costs more than the combined value of all wastewater, stormwater and bridge infrastructure in Canada):

https://www.cityfloodmap.com/2018/05/are-lids-financially-sustainable-in.html

3) Cause problems with infiltration in flood-prone areas, actually making flooding worse, as per recent comments by the Ontario Society of Professional Engineers in their official comments on the draft Watershed Planning Guidance:

https://drive.google.com/open?id=1dNFzxZxlzxUx-g9DzvVHSvwceXhddkCq

One recent study showed that permeable pavement would have a 308 year payback period based on current municipal stormwater funding models:

https://www.cityfloodmap.com/2018/03/green-infrastructure-implementation_31.html

Thank you for bringing attention to the loss graph Glenn. We should note that IBC (not a third party) still makes claims about storm frequency as in this article and there appears to be no appetite to correct or qualify that statement:

https://www.canadianunderwriter.ca/insurance/new-ibc-flood-model-shows-1-8-million-canadian-households-at-very-high-risk-1004006457/

The end result for non-technical audiences who have all seen the unadjusted loss chart and heard the very common climate change explanation is confusion and mis-guided priorities for adaptation.

PS – Even Justin Trudeau said 100 year storms are happening every 10 years after last years’ Gatineau flooding – it took the PMO over a year to respond to me and suggested he meant future storms will be more severe, and passed the question on past storms to the Environment Minister. If we do not focus on the causes of the loss increases and blindly accept what non-technical people say on climate and rain trends we could mistakenly oversize infrastructure to the point of wasteful diminishing returns that have the adverse effect of delaying implementation of the most cost-effective and rightly-sized infrastructure.

PPS – the good news is we are all trying to achieve the same thing … some of us are not paying close attention to the proper data in making comments on causes for increased losses and in prescribing solutions to reduce them.

Follow-up question .. it would be worthwhile for IBC to comment on how the change in data sources post 2007 affect these value in the chart. Since CatIQ data perhaps includes small events too, even notable events between $10M and $25M that are collected, are those events adding to the total in a manner that “various company surveys” did not up to 2007?

Also when ICLR uses this graph (like the author did for the 2016 Association of Municipalities Ontario Plenary talk (slide 8) https://www.amo.on.ca/AMO-PDFs/Events/16OWMC/PlenaryMcGillivray.aspx) and highlights the difference in losses pre and post 2008, it would be worthwhile noting the changes in data sources / methods noted in this article. Does it affect the trend? Is it a coincidence that the big noted change in losses corresponds to the change in data sources/methods?

In the author’s AMO presentation noted above (slide 19) the top answer to the question “Why are losses rising?” is given as “More people and property at risk” .. given that is essential the growth factor, why would IBC not want to “go there” and explain the influence of growth on losses, the top listed factor? Others routinely make this growth adjustment.

We should all agree that users of the graph “would then be expected to apply rigour to show a true underlying tendency and prove a cause”. Given that ICLR has listed climate change as one of the factors affecting losses (the author’s AMO plenary slide 19), could it apply this rigour to support/deny the “Telling the Weather Story” statements on climate change-related shifts in extreme weather? As noted in my comment above, that climate change-related frequency shift is not shown at all in official national datasets:

https://www.slideshare.net/RobertMuir3/storm-intensity-not-increasing-factual-review-of-engineering-datasets

So ICLR should also ‘prove a cause’ for the various loss increases it has identified, for example (#1 more people/property at risk, #2 aging infrastructure, and #3 climate change), by adjusting losses for growth to see how #1 affects trends, by working with municipalities to understand if aging (or more likely intrinsic age-related capacity) affects losses (it does https://www.cityfloodmap.com/2018/03/construction-era-infrastructure.html), and by reviewing the “Telling the Weather Story” frequency shifts or other info being relied upon for including #3 as a factor in increasing losses). And then work closely with municipalities and add cause #4 of urbanization/intensification. We can measures increases in impervious cover of many percentage points over a decade and 1000% over many decades.