Why coastal flooding is essentially uninsurable

0 March 16, 2023 at 4:12 pm by Glenn McGillivray For the vast majority of the existence of Canada’s property and casualty insurance industry, overland flood was deemed to be uninsurable for Canadian homeowners. While commercial entities have been able to purchase flood insurance for decades, it was only eight years ago that overland flood cover was made available for private residences.

For the vast majority of the existence of Canada’s property and casualty insurance industry, overland flood was deemed to be uninsurable for Canadian homeowners. While commercial entities have been able to purchase flood insurance for decades, it was only eight years ago that overland flood cover was made available for private residences.

Numerous Canadian insurers now offer an overland flood/comprehensive water product, to the point where many (maybe all) provincial disaster financial assistance programs now warn residents that they may not receive disaster assistance for flooding because it is no longer uninsurable for most properties.

Canada was deemed to be the last G7 country to offer some kind of overland flood insurance for homeowners and likely was also the last G20 as well. It remains the only G7 not to have a solution for homes at high risk of flooding.

As part of this last point, coastal flood risk remains uninsurable (most Canadian flood insurance policies stipulate that only freshwater flooding is covered under the policy). Only one company currently includes salt water coastal flooding in its flood/comprehensive water product.

In order to understand why coastal flood risk is not insurable in Canada, it is helpful to look at the factors that must exist to make something insurable, then apply these to coastal flooding.

Several sources of information can be used to determine if something is insurable or not, each one being slightly different than the others. For our purposes, we will go with the following list.

Elements of insurable risk

Large numbers of exposure units (a.k.a. mutuality)

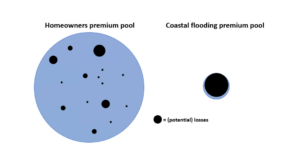

In order for something to be considered insurable, with coverage being relatively easy to find and affordable, there must be a large number of similar exposure units in order to get proper spread of risk. When there isn’t a proper spread of risk, we end up with a problem known as “adverse selection.” To illustrate this, let’s use the example of coastal flood insurance. Adverse selection happens when coverage is demanded only by those who have high exposure to that type of flooding, leading to a tainted pool of insureds (i.e. because only those at direct risk would purchase the coverage). It often also leads to coverage too expensive for the average homeowner to be able to afford, making the product economically unviable.

Traditional homeowners (i.e. “fire”) insurance works quite well because there is a (very) large number of exposure units with very similar risk profiles spread out over very wide geographic areas, making it very unlikely that an insurers’ entire book of homeowners policies would be put at risk from a single loss event (this, of course, depends on the size of the insurer and assumes that the company actively manages its accumulations and has a robust cat reinsurance program in place. Small, regional insurers are at greater risk). Although some differences exist with regard to fire risk — between urban and rural insureds, for example — there is a good understanding of the number of homes lost or damaged by structural fire each year, or subjected to theft, sewer backup, etc. This allows insurers to lump a variety of different homes from different places into a portfolio of homeowner policies where the insurer has a fairly good idea of overall annual loss experience and of costs and profit margin. Losses here can be from a range of perils (each with its own probability function) and are more spread out and random.

One of the issues with coastal flooding is that, relative to the number of homes in the country, very few people reside on low-lying areas near Canada’s ocean coasts. This means the pool of insureds would be relatively small, meaning a small “bank” to draw from in order to pay losses. This would make a standalone coastal flood product economically unviable from an insurer’s standpoint.

Further, there would be great concern about adverse selection taking place — i.e., only those with direct exposure to coastal flooding would purchase the product, resulting in very large losses for an insurer in the case of a major coastal flooding event (like storm surge from a hurricane).

This is the primary reason why landslide and permafrost melt are generally not insurable in Canada. Relative to the whole, very few Canadians are exposed to these perils, meaning only those at direct risk would purchase the coverage. This would make the coverage too expensive to buy but also not appealing to insurers due to the concentration of risk and the potential for large losses, particularly with regard to subsidence caused by permafrost melt driven by climate change. Further, if such coverage was included in standard homeowners policies, there would be a requirement for a large degree of cross-subsidization by those not exposed to the peril.

Historically, it’s been argued overland flood is not insurable in Canada because only those (relatively few) Canadians who live on flood plains would be at risk; hence, only they would want the product, making it too costly and exposing insurers to almost certain losses. The argument was somewhat specious, particularly given that overland flood was being insured in scores of other countries worldwide for decades and Canada was one of the last major industrial powers to cover the peril.

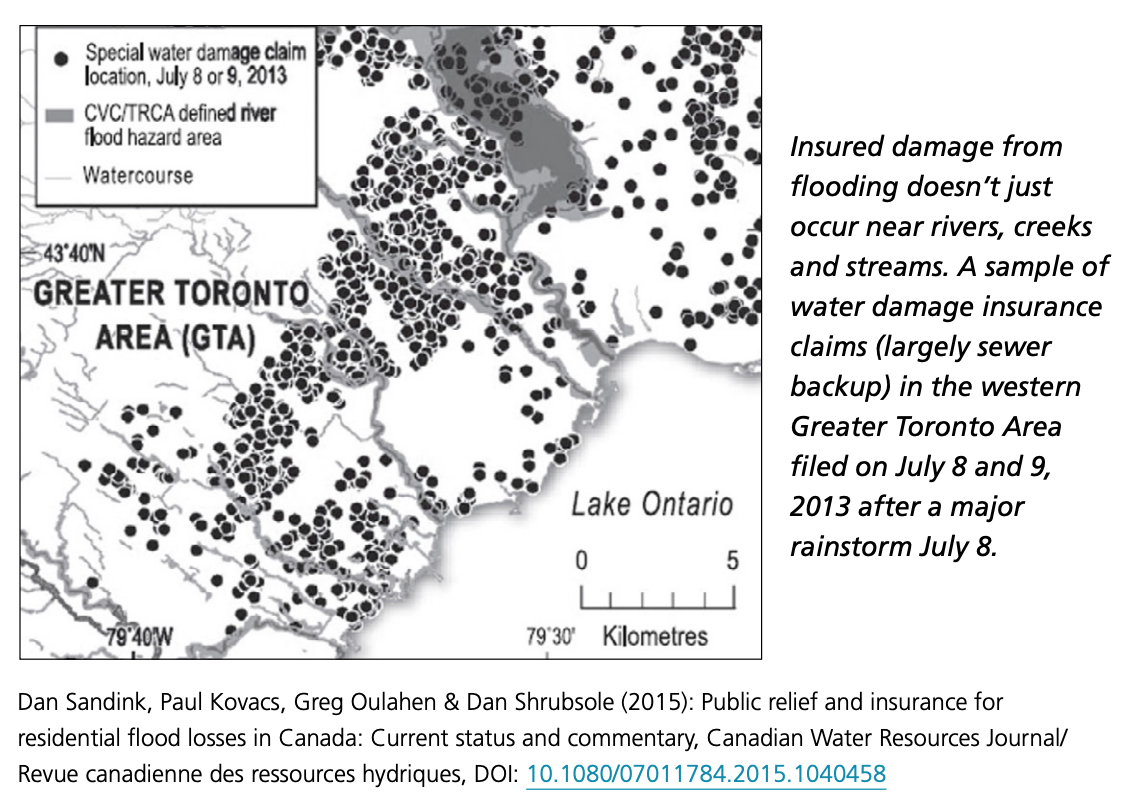

The view on insurability of flood changed partly as our understanding of the flood peril changed (i.e. there was growing understanding that overland flooding occurs not only close to bodies of water, but also by random extreme rainfall events that had nothing to do with waterways, putting essentially all Canadian homeowners at risk. Now, some places in Canada enjoy flood insurance market penetration of close to 60% as a fraction of fire insurance policies by number of policies (see here for more on market penetration of flood insurance in Canada).

The view on insurability of flood changed partly as our understanding of the flood peril changed (i.e. there was growing understanding that overland flooding occurs not only close to bodies of water, but also by random extreme rainfall events that had nothing to do with waterways, putting essentially all Canadian homeowners at risk. Now, some places in Canada enjoy flood insurance market penetration of close to 60% as a fraction of fire insurance policies by number of policies (see here for more on market penetration of flood insurance in Canada).

Of course, the industry’s view on the insurability of flood also changed as flood insurance models were developed and shared with the industry.

Two ways of addressing the insurability of coastal flooding include:

- folding coastal flooding into coverage for all other types of flooding, thus spreading the risk among a wider pool of insureds

- working with government to develop a solution for those at high risk of flooding, like through a public pool

The first option is not as simple as it sounds and presents several challenges, including a requirement that those at very low to low risk of flooding cross-subsidize those at very high or extremely high risk.

Definable and measurable loss

In order for something to be insurable, a loss should be definite as to the cause, the time it occurred, where it happened and amount of the loss.

These all can be determined in the case of coastal flooding. In and of themselves, they don’t appear to be a major barrier to insurability.

Determinable probability distribution

In order for something to be insurable, insurers must be able to determine the probability of a loss (i.e. determine how common a loss may be or how rare).

When Canadian insurers entered the flood insurance market in February 2015, they (obviously) had no historical flood loss data to go on. Insurers used models to determine what could be. But generally they were operating on a “go-forward” basis, collecting loss data as they went. This process continues.

The same would have to occur if coastal flooding were to be covered. But this would have to be with the understanding that coastal flooding is far more probable than, say, urban pluvial flooding at a particular address caused by an extreme rainfall event.

This lack of data provides for a lot of challenges, but generally is not in and of itself a clear barrier to insurability.

Calculable chance of loss

In order for something to be insurable, insurers must be able to calculate the average frequency (total number) and average severity (cost) of losses from an event.

This, coupled with the previous point about probability distribution, underscores a fairly big problem for viable coastal flood insurance. At present, we don’t have adequate coastal flood hazard maps or coastal flood models needed to do a proper job of it. Nor do we know exactly what climate change will mean to current coastal flood risk.

And while we could say many of the same things when we talk about current flood insurance in Canada — in the lead-up to 2015 and even now, to some degree, we still have data problems regarding flood risk — the much bigger risk pool helps to even out some of the uncertainty. That wouldn’t be the case for coastal flooding, where the risk is far more concentrated and there are still too many unknowns.

Because of the greater risk surrounding coastal flooding, offering standalone coastal flood insurance could be fatal for an insurer. Further, simply folding coastal into a larger flood insurance/comprehensive water policy would likely require greatly imbalanced cross-subsidization between, say, a homeowner paying a flood premium in a downtown urban address that is away from a river and someone living right on the coast in, say, Atlantic Canada.

Fortuitous loss (a.k.a. randomness)

To be insurable, the loss must be random (i.e., it may or may not occur in the future). This is key, because a homeowners insurance policy is not a property maintenance contract or a warranty.

The main issue with assets located on a coast is that, although all won’t necessarily certainly flood, many will; and, over time, many will flood repeatedly. For some properties, the certainty is close to 100%; thus, the fortuitousness or randomness would be all but gone. Then the policy has stopped becoming one of insurance and has become one of maintenance, which flies in the face of the basic tenets of insurance and concepts of insurability. The “sudden and accidental” becomes “regular and expected” or predictable.

Non-catastrophic loss

Non-catastrophic loss

In order for something to be insurable, losses must be spread throughout the group and cannot happen to all or most group members at the same time. If they did, a major loss could be fatal to the insurer.

Because of the smaller risk pool and the concentrated nature of the risk itself, it is far more likely that a coastal flooding event – like the kind generated by post-tropical storm Fiona in Atlantic Canada last September – would be catastrophic, potentially affecting a large majority of members of the risk pool.

Again, this risk could be mitigated by folding coastal flood into a broader flood/comprehensive water product. But, as noted, this would create greatly unbalanced – many might say hugely unfair – cross-subsidization with those at very low or low flood risk paying for those at very high or extreme risk (as is currently the case with taxpayers paying into disaster assistance).

Premium should be economically feasible

In order for something to be insurable, the insurance consumer must be able to afford the premium.

If an insurance product is only offered by one or two carriers, and it is so costly as to be unaffordable for most, the risk cannot really be considered insurable. Prior to launch of overland flood insurance in Canada in 2015, homeowners could purchase flood insurance from specialty carriers at a very high premium. This coverage would not be considered easily available or affordable.

Short of folding coastal flooding into a broader flood/comprehensive water product (and creating unfair cross-subsidization as a result), coastal flooding contains too many barriers to make it an easily accessible and affordable standalone product.

Conclusion

Of the seven conditions above that make something insurable, only one or two create no or just a small barrier to insurability for coastal flood. Unfortunately, the remainder pose large challenges to the insurability of coastal flood risk as a standalone product. And these barriers, if ignored, could be fatal to an insurer who writes enough of the risk and is not properly reinsured.

Some risks are better left to government. And in the case of flood, these include high-risk homes, including those on Canada’s ocean coasts.

By beginning to offer overland flood insurance some eight years ago, and given the growing market penetration since that time, Canada’s insurers have taken a huge burden off of provincial and federal disaster assistance programs and, thus, off the backs of Canadian taxpayers.

But taking on the whole burden would be fatuous, and possibly lethal.

Feature image courtesy of iStock.com/Sjo

Note: By submitting your comments you acknowledge that insBlogs has the right to reproduce, broadcast and publicize those comments or any part thereof in any manner whatsoever. Please note that due to the volume of e-mails we receive, not all comments will be published and those that are published will not be edited. However, all will be carefully read, considered and appreciated.

Leave a Reply